To BE* or not to BE*

03 Nov 2021

*Best Estimate

There are many ways to describe the year that was 2020, some of which not suitable for publication. For companies reporting significant pension obligations during those turbulent times, 2020 presented somewhat of a challenge for assumption setting, with tensions arising between the need to be market-based and the overriding ‘best estimate’ requirement such that financial statements are a true and fair view of a company.

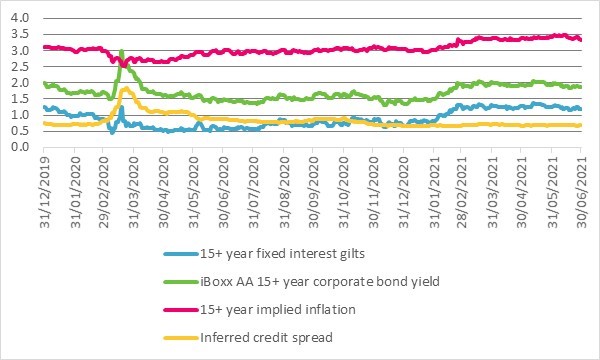

The chart below shows key IAS19 metrics over the last year and a half. Those reporting around 31 March 2020 would have benefited from a significant, though short-lived, spike in credit spreads which served to suppress the reported value of their obligations. Everyone else was not so lucky, making comparisons between financial statements challenging for those without a good grasp of pensions.

In the context of discount rates, could the transient spike in March 2020 really be considered ‘best estimate’, particularly when by the end of the reporting exercise it was clear that spreads had significantly narrowed again? Perhaps not. In any case, IAS19 is rather explicit in prescribing the use of market corporate bond rates and so companies either continued with their previous approach or refined somewhat to more closely align with the intentions of the standard (for example by excluding oddly behaving bonds that could reasonably be considered ‘not strictly corporate’).

For FTSE 350 December reporting the range of reported discount rates (from 1.2% to 1.5% with an average of 1.4%) was actually 10bps narrower than it was in 2019. It’s striking to note the level of conformity despite a very volatile year. This is likely in part driven by tougher scrutiny and benchmarking from audit firms, following the FRC’s review of their practices.

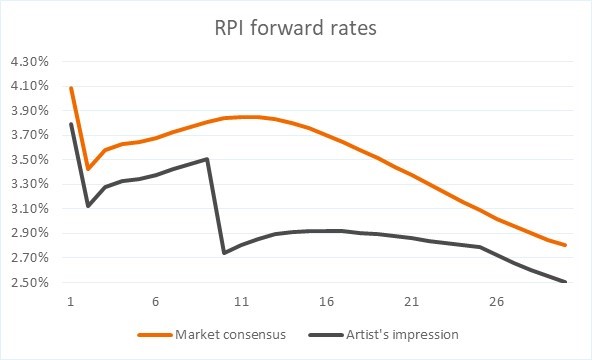

But nowhere is the tension between market-based measures and best estimate requirements more glaring than inflation. It is now well understood that RPI will be aligned with CPIH from 2030 (although will still be called RPI to avoid a significant mess). CPIH is a measure which has, for structural and calculation reasons, tended to run at c1% below RPI in recent history. Armed with this information any reasonable person, if asked to paint a picture of RPI into the future, would probably include a noticeable step-change downwards from 2030. Market consensus seems to differ:

The difference is stark. The issue is further compounded by the lack of a sufficiently deep liquid market for CPI, and so the CPI inflation assumption tends to be set by applying a fixed downwards adjustment to RPI. So if we take market RPI and recognise that the gap between RPI and CPI (which for simplicity we’ll assume is the same as CPIH) will shrink significantly from 2030, we end up with a CPI curve featuring a pronounced jump up at 2030 … despite the fact CPI isn’t changing! Given most companies’ pensions obligations are linked to inflation of some form, the results could be hugely magnified liabilities.

Yet, this is what most companies seem to be doing. December 2020 reporting from the FTSE 350 suggested typical downward adjustments to market RPI of just 20bps, in line with pre-reform practice. At the same time, the average RPI/CPI “wedge” reduced from 90bps to 70bps, leading to a methodology that inevitably created higher CPI assumptions than the previous year, with around a quarter of companies reporting a CPI assumption of 2.4% to 2.5% - well above the Bank of England’s long-term target of 2%. Why?

- The general consistency requirement of financial reporting means companies, and their auditors, don’t generally like to be outliers. Benchmarking against others is done retrospectively and so there is an inherent anchoring to past practices which may not be helpful when something substantive has changed.

- There is comfort in markets and a view that they at least reflect some level of consensus as to future rates of inflation.

- FRC scrutiny of audit firms has created significant hesitancy to sign off on assumptions significantly different to financial markets and past industry practice, particularly when these changes tend to reduce liabilities.

I can see plenty of merit in the views above. Nevertheless, I’d also stress the following:

- Following a herd doesn’t necessarily get you to the right place. And if the herd all moves in a similar direction, the outlier problem goes away.

- Historically the RPI market has been relied upon although has been recognised to suffer from supply/demand distortion. This has typically been addressed by use of “inflation risk premia” adjustments of c20bps. Now that we have a discernible step-change from 2030 that isn’t being reflected it perhaps suggests a particular, and more serious, supply/demand issue at the long-end of the curve that may well warrant a change in approach to assumptions setting.

In Hamlet, Shakespeare writes: “To be, or not to be? That is the question — Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And, by opposing, end them?”. The idea of whether it is better to live or to die.

Okay, so it’s not quite life and death here. But I’d encourage companies not to simply keep following past practice (suffering those slings and arrows) but to take up arms. Or rather, engage with these challenges, form views and have robust conversations with advisors and auditors. The industry will be all the healthier for it.

0 comments on this post